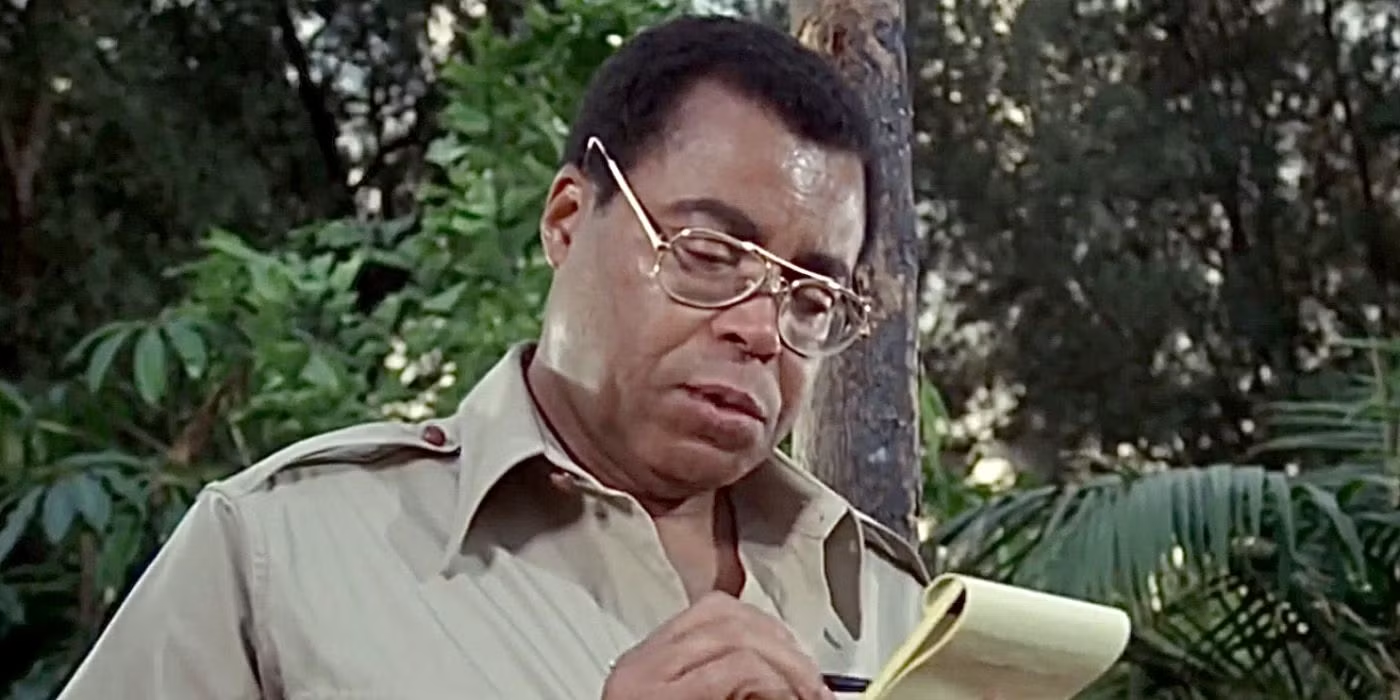

These words, spoken by James Earl Jones as Alex Haley, were repeated by my husband, Wendy, when we located the grave of my third great-grandfather, Adam Lewis Bingaman.

While not as fantastical (nearly impossible) nor as profound as finding Kunta Kinte through the words of the Gambian griot, they felt right in the moment.

To be honest, the tombstone was pictured on Find-a-Grave, the online database of gravesites around the world. Yet, finding it in the Metairie Cemetery of New Orleans resembled the proverbial needle. The haystack consisted of 127 acres of more than 7,000 intricately-ornamented marble mausoleums as well as tombs reminiscent of Egyptian pyramids and Greek temples.

Not surprising, then, that the thin slab darkened with age, propped up by what looked like footstones “borrowed” from other graves, did not stand out.

When my sister visited New Orleans several years ago, I asked her to look for Bingaman’s resting place. Having good sense, she consulted the cemetery’s office who informed her they had no record of the name. Why not? I knew he’d died in poverty. Was he squeezed into the plot of some kind-hearted friend, therefore not registered in his own name?

To be honest, someone of his background and prominence in the early nineteenth century would require one of those ostentatious crypts. He descended from one of the earliest families of Natchez, Mississippi, graduated top of his 1812 Harvard class, was speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives, and president of the Mississippi State Senate. His prominence as a turfman was legendary. So what happened?

Over the years, Adam Bingaman fell further and further into debt. Whether via his horse racing ventures or just poor management, I can’t say. The Civil War nailed his financial coffin. He lost his Natchez plantation and moved to New Orleans where he lived with his concubine, a Free Woman of Color, Mary Ellen Williams, and their children. There, he boldly strolled the streets with his mixed-race family. Causing a sizable scandal, I’m sure!

He and a son-in-law, St. Felix Casanave, fought fiercely in court over the inheritance of Bingaman’s son with Mary Ellen Williams, James Adam Bingaman, who had perished in an 1866 steamboat explosion. The estate was considerable–$25,197 which translates to $506,791 today.

A Person of Color whose family were prominent undertakers, Casanave lost.

Fast-forward three years. Adam Bingaman died with little beyond two beloved books from his Harvard days. Whatever else he had, he left to James’s little sister, Elenora. I guess under the circumstances, the family appealed to their relative, St. Felix Casanave to help with the burial.

A cousin of mine has been researching Adam Bingaman, preparing to write a book about this complex man. He sent me a rather obscure 1876 newspaper feature, describing the “preciously guarded” new process of embalming. The reporter toured a building in the corner of New Orleans’s Catholic Cemetery #2 (now known as St. Louis Cemetery #2) where the process took place. The embalmer, G. Casanave, showed him around. The journalist wrote:

“We there found forty or fifty coffins inclosing (sic) the defunct remains of embalmed humanity, among which were those of Colonel Bingaman, a celebrated turfite in his time.”

What the hell? Adam Bingaman had died in 1869, seven years before this article was written. How long had he lain there, a showpiece for the Casanave embalming skills? Was it some macabre form of revenge? My cousin speculated Bingaman perhaps had ended up buried in that cemetery off St. Louis Street.

But, for my birthday trip, Wendy had dug a bit deeper. He discovered the very plot in the Metairie Cemetery where Adam Lewis Bingaman was finally laid to rest.

Who had cared enough to, at last, place his casket there, only feet from the course on which his many horses had raced? How many years had it taken?

“I found you!”

Wendy’s words overwhelmed me. My third great-grandfather, whom I’d previously felt little connection with, had been forgotten.

“I came,” I told him. “I’m here.”

To my own surprise, I leaned my head against my husband’s chest and cried.

RESOURCES

John T. Lloyd & Co, publisher, Explosion of the Steamer Louisiana 1849 in Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory 1856 , marked as public domain, details on Wikimedia Commons

La Carmina, Roadtrippers. (2020, September 29). Crying dogs and flaming tombs at Metairie Cemetery, one of New Orleans’ most grandiose graveyards. Roadtrippers. https://roadtrippers.com/magazine/metairie-cemetery-new-orleans/

Leave a comment