“We’re all ghosts,” wrote Liam Callanan. “We all carry, inside us, people who came before us.”

I don’t know if that’s true. My whole life I’d imagined my ancestry as ordinary—until I researched my Pryor roots and the surprises spilled!

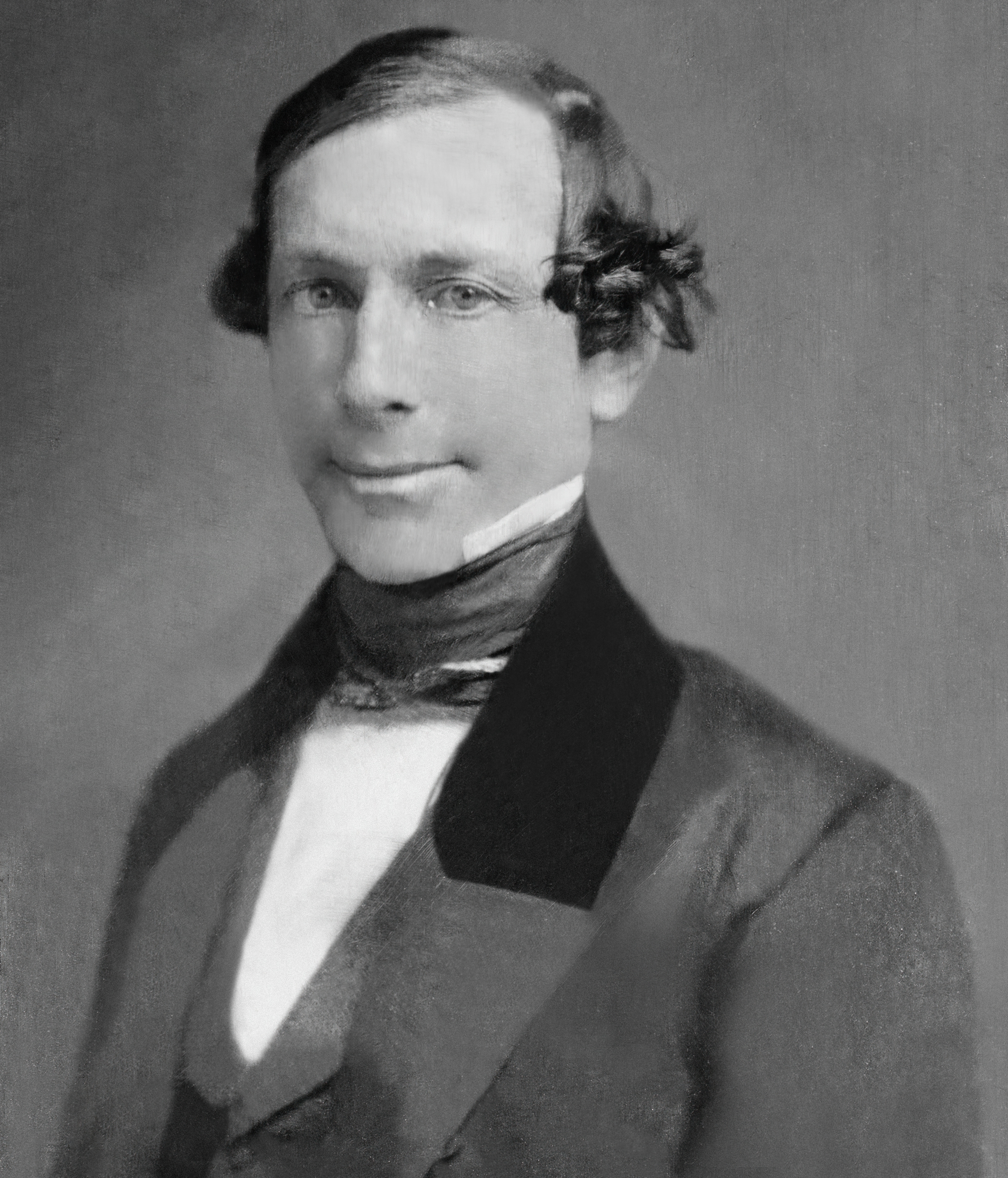

My grandfather, Luke Pryor, and I were remarkably close. He told me story after entertaining story of his life, but he never relayed anything about his father or grandfather. Did he know of this great-uncle, also named Luke Pryor?

I discovered the man was a United States senator from Alabama after the Civil War. For fun, I scoured old newspaper articles about him.

The family had moved from Virginia to the “Cotton State” in 1820 after a reversal of fortunes. My great-great-grandfather, Ben, was eight years old when his little brother, Luke, was born shortly thereafter in a local inn. Unlike for the baby Jesus, there was room.

When Luke was thirteen, he joined his brother, Ben, a prominent horse trainer, for a week of racing and cockfighting (it was a different time) near Huntsville. In the middle of the night, Luke was awakened by screams and hollers. Running from the barn where he guarded horses, he witnessed a remarkable celestial phenomenon. Over 30,000 ‘stars fell on Alabama.’

A now-famous song was based on this incredible meteor shower. As one might expect, people thought it was the Judgement Day and fell to their knees, confessing lifetimes of sins. A local Georgia newspaper wrote that “dust-covered Bibles were opened and that dice and cards were thrown to the flames.”

Luke Pryor recounted this memory throughout his life.

He grew up to become a lawyer and was, by all accounts, unassuming. Briefly elected to the state legislature for one term in the 1850s, he successfully brought a railroad line to his area. Then, at age sixty, he was chosen by the governor to fill a U.S. Senate seat following the death of his predecessor.

He didn’t ask for the job and much of Alabama was outraged. Basically, they asked, “Who the hell is this guy?”

Here are a few comments of the day:

“Mr. Pryor is an unknown man but will do to keep the seat warm until the Legislature meets next winter…”

“Mr. Pryor has had little or nothing to do with public affairs—especially since the war, and a good deal of opposition to it has been expressed, even by his warm, personal friends.” [What was their definition of ‘warm’?]

“Mr. Pryor has not voted since the war. If such is the case, Governor Cobb…had no right to make the appointment of such a drone out of the hive of so many busy workers.” [Ouch!]

But here’s the kicker:

“That Mr. Pryor is a worthy gentleman and a good lawyer cannot be denied, no more than that he is facetious, and eccentric, and outré in his appearance.”

Facetious? Eccentric? Outré in appearance? Sounds quirky–my favorite kind of person!

His greatest asset seemed to be that he’d agreed not to run the following November.

When he arrived in Washington, the Norfolk Landmark wrote “Hon. Luke Pryor, the new senator from Alabama, was once a humble ox-driver.” Good start.

But don’t count a Pryor out! When his time came to leave the Senate, they reportedly begged him to stay.

According to The Athens Post in Alabama, as senator, Luke “did not speak often; but whenever he rose in his place…he received an attention not usually accorded to Congressional debaters…[H]e rose above the level occupied by the mere partizan politician, and viewed every question from a national standpoint. [His] quick and correct perception…broad liberality and…noble patriotism [attracted] the admiration of all observers without regard to party lines.”

Wow! That almost sounds like a fairytale these days. Yet, it was said, “Nothing could induce him to ask the people to keep him in Washington.” He walked away.

His successor was quoted as saying, “I come to the Senate because that crank, Pryor, wouldn’t!”

Two years later and without his knowledge, Pryor was chosen by acclamation to run as a Congressman. He agreed and served one term, at the end of which, he said, “Once I am out of this, they’ll never get me back!” Even in those days, such a careless attitude toward power was rare. Clearly, pomposity was not his fatal flaw. It seems, without trying, he drew people to him.

A woman carrying her swaddled baby once stopped a newspaper columnist on the street. Proudly showing off her infant, she introduced the little fellow as Luke Pryor. In the 1883 Birmingham newspaper, the columnist wrote, “The newborn boys are all named Luke Pryor. No more George Washingtons, Andrew Jacksons, or Henry Clays.” He listed four people he knew whose sons were the modest man’s namesakes.

Luke Pryor died at home in 1900 with these final words: “Tell the people the old man fell with his face Zionward.”

My grandfather was born only six years later. Was he aware of this distinguished ancestor who shared his name? I don’t know. He never said.

Leave a reply to Luanne Cancel reply